by Bodh Maathura

“If you give me the option between higher tariffs and power cuts, I would any day accept higher tariffs because I can self-impose a power cut on myself if I can’t afford it” quipped Murtaza Jafferjee, a prominent economist, at a recent TV talk show. “…the example given is very telling” shot back Jayathi Gosh, a professor of Economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, responding to Jafferjee’s take on electricity pricing and rationing. She went on to say “…Who are the people who won’t be able to afford power? Is that what you want to do to the country? Is it to tell the poor that they don’t get electricity?” While Prof. Gosh highlights the insensitivity of Mr. Jafferjee’s argument, it does not invalidate the fact that power cuts do harm and that prices are a good way to allocate scarce resources in an economy. So, does that mean we should be okay with the poor not getting electricity?

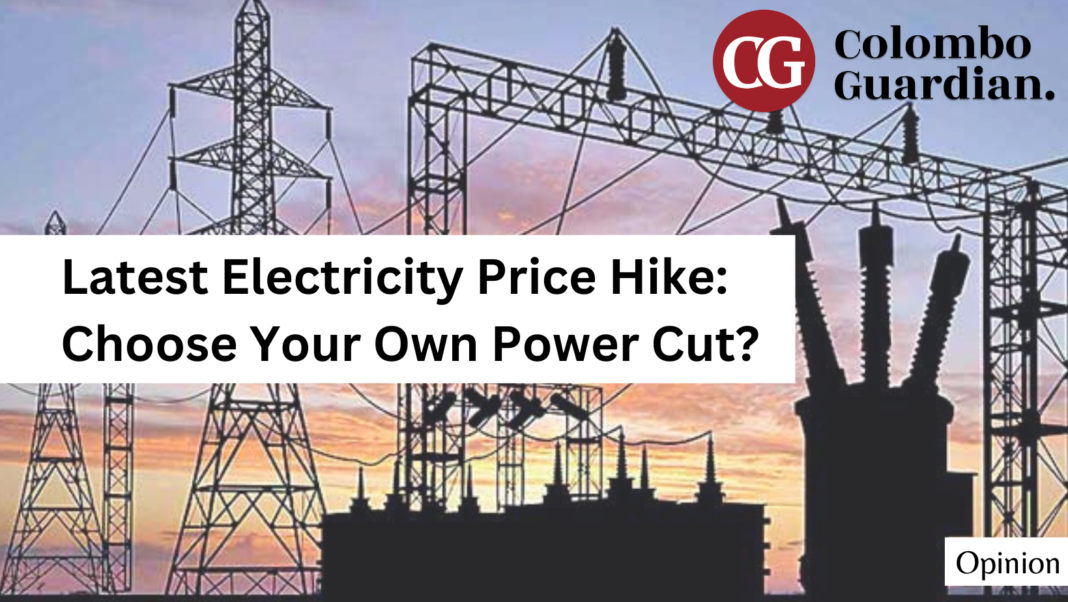

Power and Energy Minister Kanchana Wijesekara who championed the cost reflective energy prices (also an IMF recommendation) has finally succeeded, and the electricity tariffs were hiked by 66% on the 15th of February. The following day the Minister was able to announce that “There will be no power cuts from today, uninterrupted power supply will be provided all over the island”. While some celebrate this feat, another group must be finding themselves now having to decide how to self-impose the power cuts, or they might continue consuming without paying bills till the electricity connection is disconnected.

How special or odd is the hike?

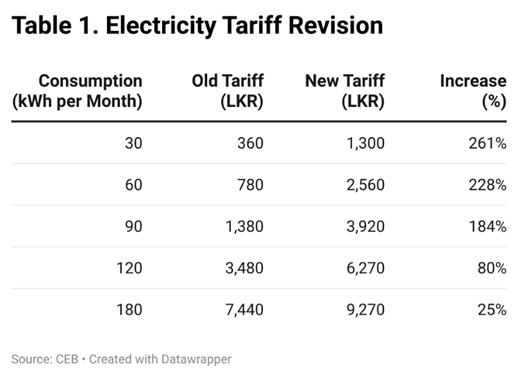

A key feature of this price hike that differed it from the previous, is the tariff hike (in percentage terms) is disproportionately higher for the lower end consumers compared to a high-end consumer (Table 1).

This tariff change has moved to eliminate part of the cross subsidy (a subsidy granted to a business activity out of the profits of another business activity) provided to the lower end users through the previous tariff rates. Using electricity tariffs as a subsidy is inefficient and seeps through to subsidize energy for the whole population and not just the poor. However, choosing to phase it out prior to establishing a well targeted welfare system that compensates the shocks created by the tariff hike will make the reform more exclusionary.

The other victim of the tariff hike are businesses, mainly the micro, small and medium enterprises. They face the choice of closing-down their business or passing on the cost to the consumer, with the hope that there will be sufficient demand at the new higher price. The rising cost of production will be detrimental for the industries producing for the local market, as it will become cheaper to import than produce the products. However, due to the existing Balance of Payment crisis, the cheaper imports will have to be curtailed, enforcing the higher prices on the consumers. The higher prices will force people to self-impose restrictions on consumption. For poverty-stricken households this will be self-imposing rationing of food intake.

Picking the right scapegoat

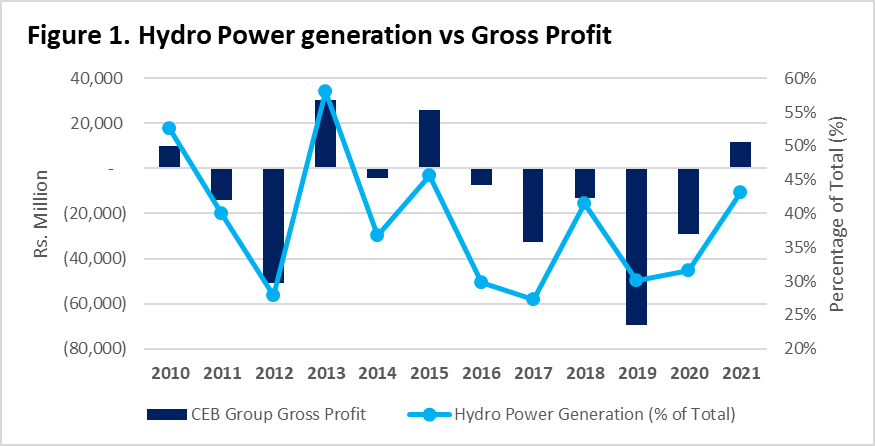

All these hardships will push people to vent their anger on a scapegoat. The easiest targets being the ‘inefficient state-owned enterprise’ and ‘their overly compensated public sector workers’ who mismanaged us into this mess. Well then there is an easy solution for that: ‘restructure the public sector’ and ‘privatize’. These scapegoats allow us to shy away from the real reason for us to be in this abyss: The electricity generation cost structure. For the past decade Sri Lanka has relied on a ‘pray for rain’ strategy to bring down the electricity generation costs. During the years the hydropower plants generated a sizable supply of power, we ended up being profitable (Figure 1). However no proper long-term generation plan was enforced to ensure sufficient power was generated with the thought of bringing down the overall cost structure.

Factoring vulnerabilities

While no plan was enforced to bring costs down there was also no risk management strategy for the vulnerabilities. The CEB balance sheet holds USD denominated debt, which makes it highly vulnerable to exchange rate fluctuations. The depreciation of the Rupee seen in the first half of 2022, directly resulted in the finance cost of CEB rising significantly. This worsened an already high financing cost that pushed CEB deeper into losses. Further, 50-65% of the energy generated requires an imported input, be it coal, diesel, or crude. This means that our energy costs are vulnerable to both global energy shocks and Exchange Rate fluctuations. While coal being an unpopular form of energy generation it is more cost effective compared to thermal which is also a large carbon emitter. If the CEB moves ahead with paying renewable energy suppliers in dollars for the energy that is produced, then both the solar and wind energy will also be vulnerable to the volatile exchange rate.

All these inherent flaws entail a cost, and that cost is now reflected on the price (or so we hope). However, these costs (prices) are still vulnerable to both the exchange rate shifts and the global energy shocks. If Sri Lanka shies away from blaming the true cause of the crisis, the energy generation cost structure, and does not address it, the consequences will be adverse: as the prices continue to rise, there will be further harm inflicted on both the poor and the industrial economy.